Tactical Urbanism, Citizenship, and the Digital Sphere

New tools for citizen empowerment

This text is the result of my intervention in the ‘Hacking the City’ workshop organised by radarq that took place in Seville, Spain, on September 2012. My goal was to think about the Tactical Urbanism concept and its ability to empower citizens, considering the possibilities that the digital sphere and the new technologies can bring to us.

Paco González, the one who handled me the invitation to this workshop, was also the one to suggest me that my presentation should be focused on answering the following questions:

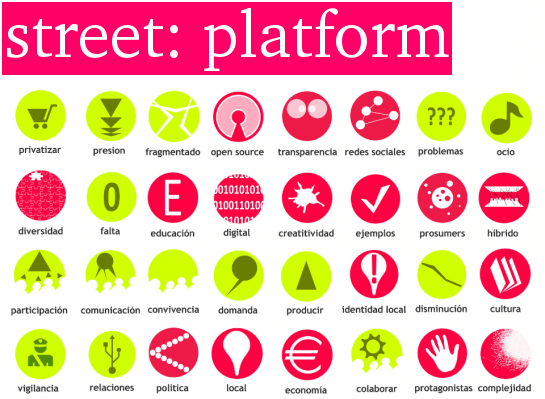

What is the meaning of the street as a platform?

How can mapping and geolocation technologies affect the concept of citizenship?

What are the changes brought by ubiquity and mobile / smartphone usage?

image by Francesco Cingolani (immaginoteca.pro) based on flickr images by garpa.net & See-ming Lee

Here are my thoughts.

With Tactical Urbanism I understand the set of actions or micro-actions spontaneously launched by citizens themselves, based on self-organization and focused on modifying or improving their habitat. As a result, the city is again understood as a space of social production the way Henri Lefebvre pointed out, and its inhabitants are now the productors of a bottom-up city as opposed to the top-down view that characterizes traditional urban planning.

Before carrying on, I would like to highlight the need of lowering the reflection about urbanism and urban models down to the dimension of the everyday. We need to think about our real lifestyle, about how we are experiencing the city and our social relations. I want to suggest the need of going down to the ‘earthly’ to avoid falling into too many theoretical issues, or what is worse, too rhetorical.

Paco Gonzalez in the workshop Urban Social Design Experience conducted along with Ethel Barahona.

One of the biggest problems in the cities is the lack of communication between neighbors. The distance and distrust that we have generated toward strangers seems to have reached a point of no return. Any problem is solved by following rules and asking specialists: we don’t count on our own neighbors anymore, not even to ask for a pinch of salt or a corkscrew.

How to start any Tactical Urbanism processes in such an acid social context?

A good starting point could be to work in processes that empower communication between neighbors. Thanks to blogs and social networks, we citizens are starting to share more and more information. A percentage of this information—even if it’s a small one—is related with the neighborhood or with the city we live in. This is the context in which Citizen Journalism, a very powerful practice to empower and visualize local identity, is starting to break through.

image source: http://thenounproject.com

The truth is that this process of continuous information exchange, in addition to its obvious value for local communities, represents the first step in the implementation of Collective Intelligence processes. We are talking about the possibility of generating new social ties based on mutual learning and the ability to collaborate and work together for projects and goals that are far from the market rules and from the quest for direct personal benefits. However, before getting to Collective Intelligence citizens need to discover and understand a new model of collective organization, that is to say the ‘network structure’ that, depending on particular cases, adds to or replaces the classic model of ‘community’.

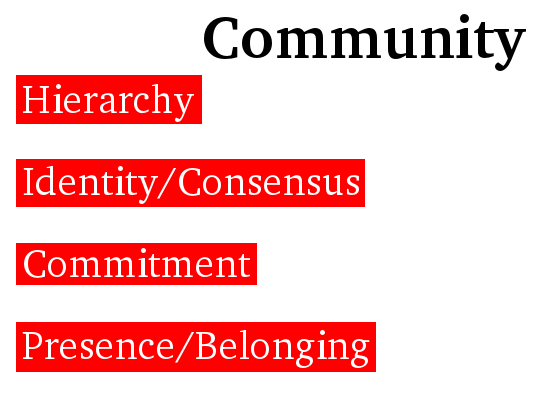

As explained in Wikipedia, a community is a set of individuals that share common elements such as a language, customs, values, tasks, an idea about the world, age, geographical location—a neighborhood for example—, social status, roles. Normally a community creates a common identity—through the differentiation from other groups or communities—that is developed and shared among its members and finally socialized.

On the other hand, a social network is a social structure formed by groups of people connected by one or more types of relationship, by common interests or by shared expertise. It can also be understood as the network that surrounds a person in the different social contexts in which he or she interacts; in this case we are talking about a ‘personal network’. A community is generally understood as a hierarchical organization that requires explicit and continuous consensus and commitment from all its members. The community often produces very strong feelings of belonging based on visibility and presence, i.e. each member has to continuously confirm his or her ‘affiliation’ with acts of presence so that he or she is still considered a member of the community. This way we see that the glue that holds this type of organization are the members themselves, their relationships and their presence.

A network operates horizontally and instead of consensus it requires common sense and balance. The members of a network don’t usually identify with it like it happens with a community. This is a very interesting aspect: belonging to a network does not require any commitment at all. The result is a greater freedom based on the much more intense and transparent exchange of information that happens within a network.

I would also highlight a very important difference: the most important thing for the survival of a community is the people, however in the case of a network it’s the information. This way, a community-based project can fail due to relational problems between members, while a network-based project often fails due to lack of transparency and information. Some urban micro-actions, although they may not have a community supporting them, can be understood as promoters of the creation of new networks.

At this point we automatically have to discuss about digital social networks, understood as communication tools for self-organizing and collective intelligence processes. The most popular ones—such as facebook or twitter—unfortunately hide many other problems related to data usage and privacy about which we could discuss for an insanely amount of time. However, it’s a fact that they have achieved an impressive mass of regular users which allows us to contact all kinds of people, a key factor for citizen empowerment.

How can we transfer into the space all this potential and this ability of self-organization and collaboration that we are now experiencing in the digital sphere?

image source: http://www.clker.com/

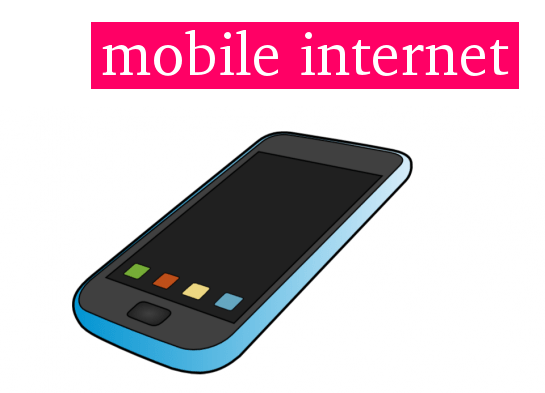

The great opportunity comes with the mobile internet and georeferencing, two things that together allow something that used to be unthinkable before, that is to associate in real time a digital identity with a particular physical space. This means that while our digital identity so far was practically ubiquitous, we can now give it a spatial dimension.

We generate what I have defined as ‘Sentient Identity’, a sensitive identity that can adapt depending on where we are. This new Digital Identity, when contextualized in real time, generates a direct connection between the space, its corresponding digital information and the people who are using it.

This hybridization and the processing of the huge amount of available information increases the ability of the space to create opportunities, to build synergies between the existing people and to encourage serendipity.

image by Francesco Cingolani (@immaginoteca) – http://www.immaginoteca.com

Thanks to the digital sphere we are now used to something that we lack in the real dimension: traceability. Most of the things that we do on the Internet leave a digital footprint associated to our Digital Identity, it gets increasingly harder to manage different identities at once.

Although this clearly has its downside—it can easily allow control over our personal information—it also has a very positive use when related to space through the use of mobile internet and Sentient Identity.

There are Social Eating services like gnammo.com that let its users organize meals at home where unknown people can participate. With Sentient Identity you can find a meal being organized by someone in your own neighborhood or even as a tourist in an unknown city. Users tend to trust these services more when they are accessed through already active accounts in existing social networks: users trust traceability. We believe that no one will do something wrong because all of his or her social network friends would find out.

image by Francesco Cingolani (@immaginoteca) – http://www.immaginoteca.com

This type of connection between digital information and physical space turns internet traceability into something physical and thanks to mobile internet it can be used in all kinds of activities.

The street as a platform

The street—when we understand it as public space—has always worked as a platform that can benefit social relations, boost commercial and production activities, and create a space for debate and political involvement.

image by Francesco Cingolani (@immaginoteca) – http://www.immaginoteca.com

Nowadays all these tasks have been transferred to other places as well as to other dimensions, a very important one being the digital dimension. As explained before, we can use the digital sphere as a tool to turn the street back into being a platform, a space of opportunities. Dan Hill started talking about this concept in 2008 in his post called ‘The street as a platform’. The street definitely is one of the spaces where we can better intervene with Tactical Urbanism actions.

In many cases we can start using the street as a platform by simply changing our behaviour.

We will now see a few examples related to this behavioral change.

image source: http://www.taringa.net

/Joint Responsibility

Involving equally: processes of collaborative social responsibility that involve institutions, enterprises, organizations and individuals

Oficina de Gestión de Muros (Wall Management Office) creates negotiation processes for the integration of graffiti art in urban walls by bringing together and encouraging discussion between local authorities, residents, district officials, urban artists and public or private funders.

The result can be seen not only on the urban wall itself, but on the development of new policies for urban art. You can also visit openwalls.org.

found through Vivero de Iniciativas Ciudadanas

/Light Infrastructures

Joining willpower to pursue goals along with others and not against each other.

Besides heavy infrastructures which are usually scheduled during urban planning from the top, Tactical Urbanism actions usually generate light infrastructures, sometimes even invisible and in any case away from big budgets and maintenance costs.

En bici por Madrid (Cycling Madrid) shows that the use of the bicycle in the capital of Spain does not depend exclusively on bike lanes being built. Through a collective effort its members create city maps to mark calm and quiet streets that can safely accommodate bicycle traffic. This invisible and flexible infrastructure (PDF) is never formalized but is available on-line and it only obtains a physical dimension when an anonymous citizen rides around the city using the information on these maps.

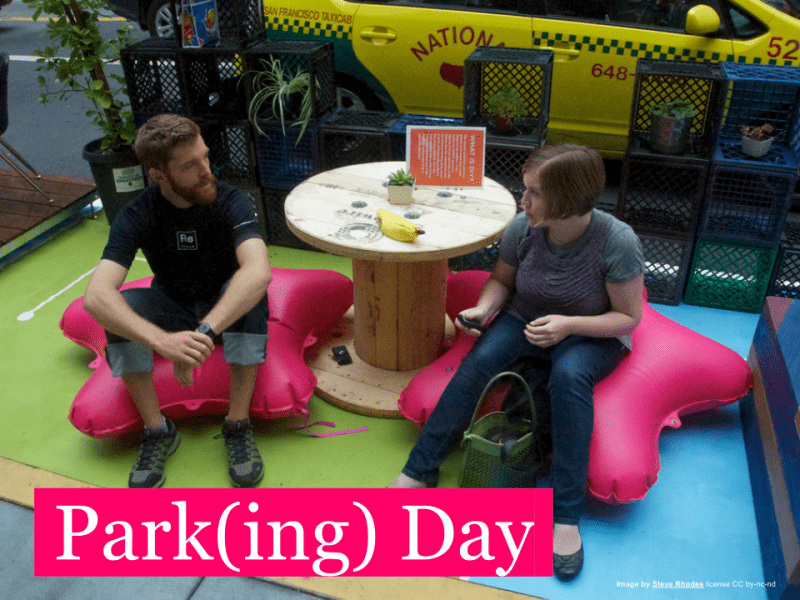

/Micro-urbanism

Creating local identity through actions which are lightweight, low-budget and have little bureaucratic requirements.

These processes don’t focus solely on an intervention on the physical space or the urban infrastructures but encourage processes of collaborative creation, promote community-based economics and rescue values to awake the local community.

PARK(ing) Day is a yearly and global celebration in which artists, designers and other citizens collaborate to transform temporarily—for one day—metered parking spots into PARK(ing) spaces, that is temporary public parks.

/Prosumer

Consuming what is produced!

Today’s society and economy are structured over a process of increasing specialization and at the same time are strictly associated to the idea that progress is only possible when it comes with economic growth. Throughout our working life we are likely to engage in the production of a limited number of things, projects or services which, in most of the cases, have nothing to do with our daily routine. This model leads us to be totally dependant on the things that other people produce. We don’t want to—or we can’t—produce on our own all the things that we need for our everyday life; we simply consume them without producing. Fortunately, today the citizen is becoming a prosumer, i.e. productor and consumer at the same time. This concept is also related to collective intelligence and collective production, since what is produced and consumed is actually the result of the work of many people, all of them prosumers. A prosumer neighborhood is able to implement open processes to solve local problems and/or contribute knowledge.

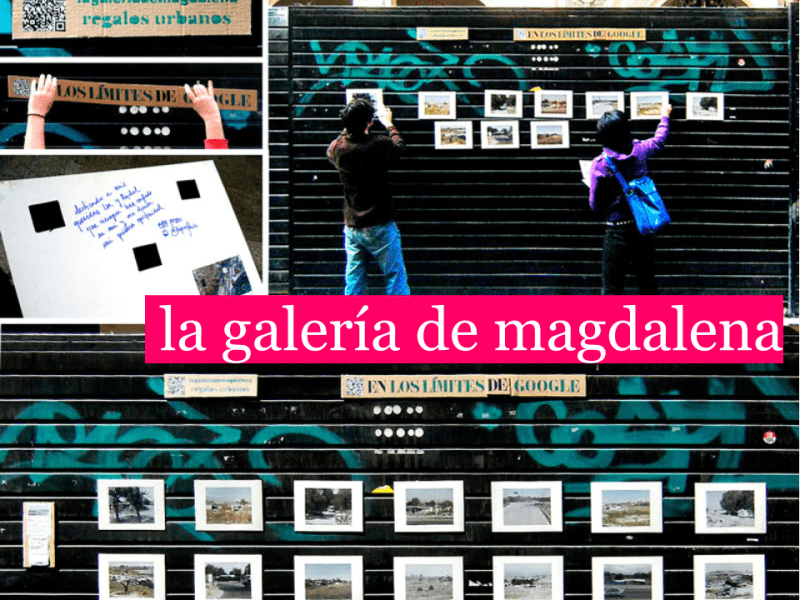

La galería de magdalena (Magdalena’s gallery) tries to take the pedestrian away from his or her reality, generate new situations between them and use the public space as a platform for art galleries with low-cost urban interventions.

picture by lagaleriademagdalena

/Co-creation

Collective thinking and action.

These are initiatives that count with few resources but with a big amount of agents so that the result does not depend on one actor, but on a process of collective intelligence and creation.

The collective Basurama (in Love we Trash), through its various practices related to municipal waste, proposes open design processes where the community discusses and reflects on trash, waste and reuse in all its formats and possible meanings. Open source, commons, offshoring and especially collaboration are implicit terms on this type of processes.

picture by basurama

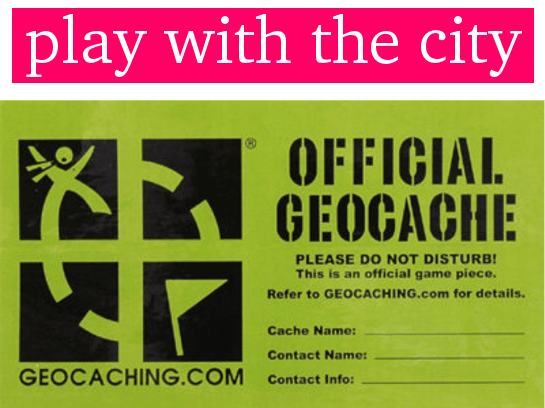

/Gamification

Playing with the city.

This term refers to the use of game mechanics for non-game contexts, so that people engage in a certain behavior. In this case we talk about actions that use game dynamics to bring people closer to the place they live in and boost interaction between neighbors. An important element of these dynamics is their ability to generate learning processes which can also be the result of a collective action, encouraging and improving social capital as a result.

Geocaching is a game that consists in hiding and seeking ‘treasures’ in any place of the world using the help of a GPS. Each player can hide objects in rural or urban locations, note down the location coordinates using a GPS receiver and publish them in specialized websites for other people to begin the treasure hunt. These websites are true digital communities where anyone can check the existence of hidden treasures near home or in any other area that they are planning to go to. The rules specify that whoever finds one of these treasures can take any object but has to leave something of equal or greater value for the next treasure hunter.

found through @Zuloark

/Collaborative Consumption

Sharing to improve how we relate to others and how we live.

The term Collaborative Consumption refers to the cultural and economic change in consumer habits characterized by the migration from a consumerism based on individual ownership to new exchange models, sharing, bartering or renting, often powered by social media and peer-to-peer platforms. This practice can mean a significant change in the way we experience the city by generating new opportunities to collaborate with our neighbors, such as consumer groups.

Gnammo is an on-line platform where both amateurs and professionals can organize meals, dinner parties or other events at their own home. Gnammo is the perfect social network to share with your friends your cooking skills or your passion for food.

found through Francesco Cingolani (@immaginoteca)

/Crowdfunding

Also known as crowd financing or crowd-sourced fundraising, is the collective cooperation of people that build a network of ‘backers’ to collect money or other resources that will sustain an initiative by a person or an organization.

Spacehive is the first crowdfunding platform focused exclusively on local urban projects.

found through Yago Bouzada (@BurningJak) from Nodos Arquitectura studio (@NodosArq)

References

This text was written using the texts, works and thoughts of Alba Balmaseda and Esaú Acosta from Vivero de Iniciativas Ciudadanas, the workshop Arquitectura en Betaby Paco Gonzalez(@pacogonzalez) and Ethel Baraona (@ethel_baraona), the workshop Entorno digital y aprendizaje urbano by Paco Gonzalez and Enric Senabre (@esenabre), the works of Zuloark, Basurama and Ecosistema Urbano and the research of Carlos Camara (@carlescamara).